Bridgerton and Normal People expose romance’s colonial hangover

There is nothing apolitical about love stories because popular ideas of romance are steeped in 19th century imperialism.

There are more than a few universally acknowledged truths when it comes to writing romance: the course of true love should not run smooth, lovers should be beautiful and readers generally prefer a Happily Ever After (‘HEA’ as it’s known in the romance community).

While love stories are still routinely sidelined by some academics and critics, the politics of love, sex and desire, and the stories we tell about them, cannot be overestimated. There is absolutely nothing apolitical about love stories because our popular ideas of romance are a colonial hangover, steeped in the reactionary values of the imperial 19th century. At this point isn’t it worth asking: what’s universal about our modern idea of love?

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Moral evil, economic good’: Whitewashing the sins of colonialism

The hidden racism of the Muslim marriage market

For ‘love’: charity-washing colonialism, fascism and genocide

I’m talking here about the hegemony of white, Anglo-American culture established through the British empire and solidified through the neo-imperialism of the United States. The culture that insists on endless adaptations of Shakespeare and Austen; churns out seemingly infinite content about the experiences of white soldiers in the world wars; and makes biopic after biopic on the lives of white historical figures. All of which are tales told at the expense of narratives that foreground people of colour.

I’m talking the kind of cultural dominance that epitomises the ‘mainstream’ and so thoroughly saturates the media that it co-opts us all, willingly or not. It is this omnipotent culture that privileges certain types of people and values certain types of stories: white, Anglo-American, middle class and heterosexual.

This is absolutely true of love stories and, if we’re to follow the example set out by the two most popular romances of the past 12 months – the lockdown phenomena of Bridgerton and Normal People – only rich, white women are worthy objects of desire.

It is not that romance narratives and love stories by and for people of colour do not exist: they do and always have. Bestselling author Alisha Rai laments the misconception that there are no South East Asian romance novelists. Black love has been celebrated as a powerful force of resistance in a racist world. Alyssa Cole’s award-winning An Extraordinary Union (2017) was famously snubbed at the RITAs, the highest awards bestowed upon romance fiction. For all their power and politics, euphoria and heartbreak, none of these stories have garnered anywhere near the level of critical and commercial engagement as Bridgerton and Normal People.

These were not just the two most popular series streamed over the past year from two of the world’s biggest content providers, Netflix and the BBC/Hulu: these were the best performing shows, globally, from Netflix and the BBC ever.

Bridgerton, a Shondaland production based on Julia Quinn’s book series (2000-2006), is a fantastical reverie of Regency England, replete with some controversial “colour blind” casting. Normal People, adapted by Sally Rooney from her novel with co-screenwriter Alice Birch, charts the on-off romance between two Irish teenagers, Connell and Marianne. While Normal People was met with almost universal praise, the response to Bridgerton has been more mixed.

‘Able-bodied, thin, wealthy and white’: Heroines since 1815

What do these two exceptionally popular shows have in common? They are love stories with romantic heroines that haven’t changed since Jane Austen published Emma in 1815: they are ‘handsome, clever and rich’. There’s another aspect to this description of the romantic heroine that goes unstated, of course: it’s a truth universally acknowledged that the ideal romantic heroine will be white.

Despite being set approximately 200 years apart, the female leads at the centre of these two romances are remarkably similar: able-bodied, thin, wealthy and white. They are also, like all good romantic heroines, virgins before they meet their appropriate romantic match (who also happen to be men, of course).

Within the first 10 minutes of the opening episode of Bridgerton, debutante Daphne (Phoebe Dynevor) has been pronounced “flawless” by Queen Charlotte and is labelled the “incomparable” of the 1813 season. Her debutante status alone tells you that she’s rich. There’s almost no discussion of Daphne’s education but she is articulate, erudite and quick-witted.

With the exception of her supposedly awkward schooldays in Sligo, Normal People’s Marianne Sheridan (Daisy Edgar-Jones) is similarly beautiful and popular with her peers at Trinity College Dublin. She is also unusually intelligent, passing the famously difficult Trinity Scholarship exams while studying History and Politics. And, although class functions differently in Ireland, Marianne’s family is very wealthy, despite the ravages of the 2008 financial crisis.

Both Daphne and Marianne have serious cultural, social and economic capital; they’d also score highly in what sociologist Catherine Hakim terms erotic capital. This is erotic capital by Eurocentric standards: extreme thinness, narrow nose, straight hair, pale skin.

‘The profits of slavery and the economic dividends of marriage’

One of the many problematic elements detected in Bridgerton’s supposedly colour-blind casting is its colourism – the preferential treatment of lighter-skinned individuals compared to those with darker skin. Effecting more than just cultural ideas of beauty, Bridgerton’s colourism also perpetuates negative stereotypes about Black people.

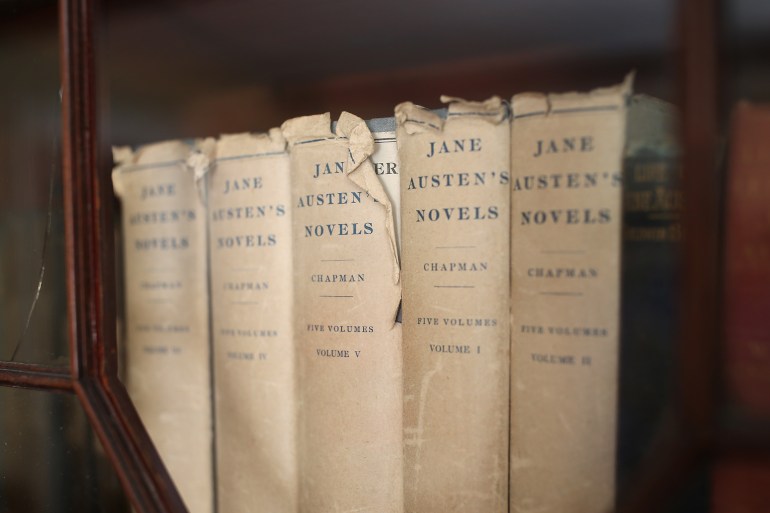

In fact, it is almost as if nothing has changed since 1813, the year Austen published Pride and Prejudice and the year in which Bridgerton is set. In the LA Review of Books, literary critic Patricia A. Matthew has noted the various nods to Austen in Bridgerton. Numerous writers have also commented on the inspiration that Austen holds for Rooney, too, and her novels of love, social manners and class.

It is often argued that Austen, and Pride and Prejudice, in particular, gave us the skeleton of the modern romance plot. But, while Austen’s novels couple acute social commentary with their love stories, in the afterlives of Austen we neuter these elements to focus almost entirely on romance. Think Joe Wright’s version of Pride & Prejudice from 2005, billed in the trailer as another film from the producers of Love Actually and Bridget Jones’ Diary.

Austen, perhaps more than any other of her contemporaries, understood that marriage was an economic undertaking. While Austen’s novels can also, in some ways, be read as offering a critique on the ambivalence of the colonial project, a successful marriage plot likely ended with a heroine firmly embedded in the heart of Britain’s colonial and imperial networks.

In 19th century England, an enormous degree of wealth was accrued and sustained through colonial exploitation and the slave trade. The legislation to abolish slavery was staggered and uneven across the Atlantic; even after the passing of the most comprehensive act, the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, various systems of unfree labour continued to persist in the form of apprenticeships and indentured servitude. Cultural historian Fariha Shaikh says “as a result of the concentration of capital and wealth, only a comparatively small number of people got rich from the profits of slavery, but its legacies of compensation, apprenticeships, and forced displacements are significant”.

Scholars such as Edward Said, Corinne Fowler, Caroline Bressey and Catherine Hall have been clear about how “the slave trade and slavery were supported by a host of other activities which were crucial to the development of the British economy in the late 18th and early 19th century.” The academic Sarah Comyn tells me how Austen’s novel Mansfield Park (1814) “intertwines the profits of slavery and the economic dividends of marriage with the fate of the novel’s protagonist, Fanny Price”.

Austen wrote one character of colour, Miss Lambe, in Sandition (1817) but Austen’s untimely death left the novel unfinished. Although the producers of PBS/ITV’s Sandition (2019) gave Miss Lambe a significant role, we just don’t know what Austen’s complete plans were for this character. In her book, Political Economy and the Novel, Sarah Comyn suggests Miss Lambe is a “seductive site of speculation” on the marriage market, as were all wealthy women.

The myth of white supremacy and the ideology of patriarchal capitalism

In so many ways, the highbrow romantic heroine is a fantasy of imperialism and she survives to this day. This shouldn’t be surprising. Austen is a part of the English canon: a literary text produced within a deeply imperial 19th-century culture and shaped to a pronounced degree by the values of this culture.

“Nineteenth-century authors such as George Eliot and Charles Dickens were deeply invested in empire,” Fariha Shaikh reminds us. “Eliot had stocks in Australia, India, [and] South Africa. Dickens’s sons careered around Australia and India.” Dickens’s attitude to numerous colonial crimes “was less than palatable – even in his time”.

These colonial values – heteropatriarchy, European imperialism, racism, white nationalism – linger in our present moment. Within the UK and Ireland, the politics of Brexit, the treatment of efforts to decolonise British education, the crisis over “rewriting history”, the recent “Report of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities” and the appalling treatment of Meghan Markle tell you everything you need to know about these colonial values.

Austen was writing for a particular audience: predominantly heterosexual, white, English, middle-class women. Behind this imagined reader lies a whole set of assumptions. Firstly, that she’d like to see an idealised version of herself as the heroine and, secondly, what and who she might find attractive. While Austen was absolutely doing something radical in articulating women’s wants and giving them a space to indulge their desires, these desires were shaped as part of a perniciously colonial culture underpinned by the myth of white supremacy and the ideology of patriarchal capitalism.

Perhaps nothing epitomises these ideas as clearly as the depiction of Marina Thompson (Ruby Barker) in Bridgerton. A poorer cousin of the wealthy Featheringtons, Marina comes from the country to stay with the Featherington family so that she too might make a suitable match and find a husband. But Marina, unlike any of her white cousins or white debutantes, had a lover back at home and comes to ‘The Ton’ (British high society) pregnant. When the series starts, Marina’s lover has been sent to Spain to fight and she is left in the position of needing to secure a husband to avoid scandal.

There has been some commentary, by writers such as Shannon Luders-Manuel, on how Marina’s character is both relentlessly commodified and hyper-sexualised as a stereotype of the “tragic mulatta”. Writing for Vox, Aja Romano argued Marina’s schemes to find a husband “puts her in an overtly predatory position which the show does little to ameliorate”. These decisions seem even more questionable when we remember that Marina, as she exists in Quinn’s book series, is just a name – not a character that readers are introduced to with her own narrative arc. The producers and writers of Netflix’s Bridgerton devised this character and her arc entirely for Netflix.

The ‘imperial female gaze’

There are problems with the male romantic leads in Brigderton and Normal People, too. The colonial values that underpin the 19th-century romantic novel are clearly in evidence in the decisions made around Bridgerton’s Simon (Regé-Jean Page) and Normal People’s Connell (Paul Mescal). You’ve probably heard of the “male gaze” and might also have heard about the more ambiguous “female gaze”. In their blatant eroticisation of Simon and Connell – the nudity, the lingering shots on their bodies – Bridgerton and Normal People make use of what we could call an “imperial female gaze”.

We can see this in the colonial thinking that marks these adaptations from page to screen. As many have noted, in Julia Quinn’s novels, Simon Basset is white; in Netflix’s version, he is Black. Historians and literary critics like Mira Assaf Kafantaris, Kerry Sinanan and Jessica Parr explore with surgical precision the racialised dynamic that “colour-blind” casting causes here. Kerry Sinanan argues “Daphne consumes Simon with her white gaze that reduces him to an artifact” and makes clear how this fetishisation must be understood as part of a longer cultural history of eroticising people of colour. For the journalist Kathleen Newman-Bremang, the intended audience is clear: “White people are going to love this,” she writes.

Just as Simon Basset’s body is presented to viewers as a commodity for consumption, people’s reaction to Paul Mescal, the actor playing Normal People’s Connell Waldron was also unsettling. Viewers became particularly obsessed with two items associated with Connell’s body: a simple silver chain and his very short Gaelic football shorts.

In Rooney’s novel, there is one sentence about a chain that Connell wears around his neck through school and university; a necklace that a friend of Marianne dismissively labels, “Argos chic”. In the BBC version, Connell wears this chain in every single scene. Audiences loved this: an Instagram account dedicated to “Connell’s chain” was created and multiple think-pieces were devoted to it. Met with bemusement in Ireland, audiences in Britain and around the world went wild for Connell’s Gaelic shorts. Paul Mescal was photographed in the streets and appeared in magazines alike in his Gaelic shorts. The fashion house Gucci made lookalike pairs that retailed for a fortune.

But, curiously, Connell doesn’t play the Irish game, Gaelic football, in Rooney’s book. In the novel, Connell plays English soccer. The BBC decision to change this reads like an effort to ramp up his Irishness for global audiences. And audiences lapped it up.

Bridgerton and Normal People might be privileging a “female gaze” but there’s more than a hint of imperial logic in the way certain men are displayed for voyeuristic pleasure. There are whole subsections of the romance genre that play exactly upon this premise, like the enormously popular “Sheikh romances” that feature love stories between white women and Arab men. Following in the template established by Edith Maud Hull’s novel The Sheik (1919), the genre relies heavily on the objectification of so-called “exotic” men and the undercurrent of Orientalist ideas about the superior beauty of white women.

Colonialism: Feminising, eroticising and fetishising

Drawing our attention to how what we might call the “imperial female gaze” eroticises both Simon and Connell is not to suggest that the experiences of being a person of colour and a white Irish man are the same: the experiential realities of being a white Irish man and a Black man are drastically different.

The relationship of Ireland to Britain and British colonialism is notoriously complex. Ireland was violently colonised by its eastern neighbour and the effects of this still structure the relationship between Ireland and Britain. The existence of Northern Ireland is a direct result of this colonisation.

But, to be clear, this history of colonisation does not mean that there was not some Irish involvement in the British colonial project. It does not mean that there is no racism in Ireland. While white Irish people have been afforded a degree of privilege on account of their skin colour, they have been, at various points, colonial subjects within the British Empire.

From the 16th century onwards, lands and people that the English sought to colonise were feminised, eroticised and fetishised as part of a broader European culture of patriarchal imperialism. This included Ireland but also numerous locations in the “New World”. And, while this manifested itself in starkly different and uneven ways across Europe’s various empires, we can clearly see the afterlife of this kind of thinking in Bridgerton and Normal People.

On Twitter, academic Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall called out the “sexualization of [Black] women” in Bridgerton, like Marina, compared to the show’s obsession with the chastity of white women. With Normal People, it’s hard not to feel like Paul Mescal has been sold to audiences as an especially Irish hunk, packaged in revealing clothes that highlight his body while labelling him as Irish. In a sea of stereotypes about the Irish, John Maguire argues for the BBC, “that of the Irish male as a romantic ideal” is a “particularly favoured” one.

Who gets to love?

With Normal People, the BBC made a strange decision to cast Marianne’s sadistic Swedish boyfriend, Lukas, as one of only two actors of colour with dialogue. In Rooney’s novel, Connell comments on how “Scandinavian-looking” Lukas is, his “hair so blonde that the individual strands look white”. That the BBC chose to cast Lancelot Ncube, a Zimbabwean-Swedish actor, in this role is significant. My friends and I discussed how uneasy we were with this casting choice given the overwhelming whiteness of the programme. The optics of a Black man tying up a white woman without her enthusiastic consent are intensely troubling, playing into a history of representing Black men as sexually predatory towards white women.

The only other actor of colour with significant dialogue is Aoife Hinds, who plays Connell’s sometime girlfriend Helen. Helen is treated poorly by Connell – who is still in love with Marianne – before he returns to his “true” love, white Marianne. Again, such a decision might have been entirely subconscious but it paints a striking image of who is a worthy romantic heroine in our cultural imagination. That Aoife Hinds was subject to racist abuse while she filmed Normal People in Dublin seems pertinent too.

We see the fingerprints of a certain set of deeply harmful values here. The insidious imprint of colonialism on Western ideas of culture leaves a legacy that is hard to opt out of. There’s a linear line from Austen’s marriage plots to our contemporary ideas about romantic success and personal fulfilment. In February 2021 the romance writer Racheline Maltese tapped into a live debate when she tweeted about the genre’s particular political – and historically complicated – relationship with sexuality and race. Romance is an arena, Maltese argues, marked by “current and ugly debates” about who gets to love: “whether BIPOC people get to be happy, whether gay people are capable of experiencing emotional connection; whether disabled people feel joy”.

Romance that goes mainstream seems so often to be laced with a certain surreptitious colonial outlook, saturated in the conservatism of the 19th century. One wonders whether this return to the imperial 19th century is what gives Bridgerton its status as a cultural project to be taken seriously, in a society gripped by what Paul Girloy terms postcolonial melancholia and nostalgia for the imperial past.

Things are changing: there’s a fraying at the edges and efforts to subvert the status quo. The films of Amma Asante are important here, especially Belle (2013), a historical romance based on the real figure of Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761-1804), the daughter of Maria Belle, an enslaved African woman and Sir John Lindsay, a British naval officer.

Normal People wasn’t the BBC’s only big romance novel adaptation of 2020, either: Vikram Seth’s novel A Suitable Boy was also adapted for the screen. Yet this, too, came laden with colonial baggage. In the Guardian, Chitra Ramaswamy argued it “may be the first Indian period drama of its kind in British TV history, but it remains an India that a British audience is used to seeing”. Tellingly, the BBC decided to commit the same amount of screen time to Seth’s epic novel, which runs to nearly 1,500 pages in paperback, compared to Rooney’s slim novel Normal People at about 260 pages. Both series clocked in at a little under 6 hours.

Meghan Markle, the first woman of colour to join the British Royal Family, has recently been denigrated and ridiculed after coming forward about the horrific racism she faced at the hands of “the Firm”. The UK, in 2021, is still not ready for a Black princess; her own love story has been anything but a fairytale. But if love stories are supposed to speak truths that are universally acknowledged, isn’t it time we got a romantic heroine something other than handsome, clever, rich and white?

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.