100 years after WWI: History lessons from the Balkans

The Balkans are still split on historical narratives about the assassination of Franz Ferdinand.

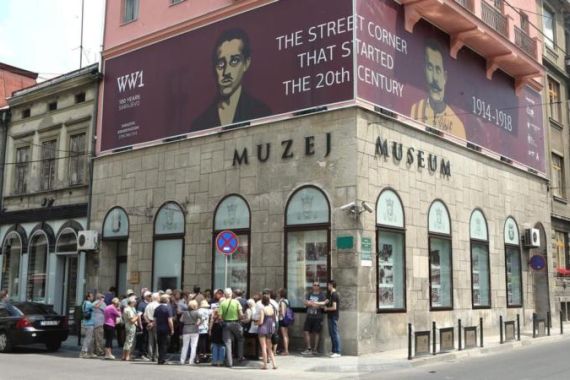

June 28 marks the 100th anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sofia in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a member of “Mlada Bosna” ( Young Bosnia ), a revolutionary or terrorist youth organisation, depending on one’s point of view. This murder is considered the watershed moment that triggered Word War I, which resulted in some 16 million deaths and 21 million wounded.

As a child, I remember going to the exact spot of the assassination and standing in “Gavrilo’s footprints”. It used to be a favourite tourist activity for citizens of Sarajevo and visitors from abroad. At the site, there was a board with these words: “From this place on 28 June 1914 Gavrilo Princip, through his gunshot, expressed people’s protest against tyranny and centuries-long desire of our peoples for freedom.”

History books in Yugoslavia taught this version of events: Young Bosnia was a youth revolutionary organisation, with an ideal of liberating the country from foreign occupation. Bosnia was annexed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire by a decision of the 1878 Berlin Congress, after nearly 500 years of the Ottoman rule. In light of these historic circumstances, where the country was passed from one imperial power to another, Gavrilo’s act was seen as the epitome of the struggle against occupation.

Today, however, the footprints are gone, and the board reads: “From this place on 28June 1914, Gavrilo Princip assassinated the Heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sofia.” Today’s version of the events presents Gavrilo as a young man, influenced by a nationalist movement, who resorted to an unforgivable act of violence.

The story of Gavrilo Princip and the Sarajevo assassination does not only show that one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter. It also shows that the definition of the two changes over time, depending on the political convictions of the governing authorities.

The truth, as always, lies somewhere in the middle, shaped by historical context and ideals of the time. This middle-ground version, sadly, never finds its way to history books which now more than ever tend to poliarise and instil divisions in public opinion on the Balkans.

History lessons today

A study by BIRN and the Centre for Democracy and Reconciliation in South Eastern Europe found that contemporary history books in schools across the Balkans present assassination in quite different ways. In Croatia, history books portray Serbia as the main war-monger who had ambitions for territorial expansion, and Mlada Bosna is presented as a Serbian terrorist organisation. In Serbia, on the other hand, history books indicate that the Austro-Hungarian Empire used the assassination as an excuse to start a war it had long planned.

The most interesting situation is in Bosnia, which has three history curricula. The Bosniak and Croat history books emphasise Princip’s nationalism and links with Serbia. In Republika Srpska, he is a freedom fighter and the Austro-Hungarian Empire is blamed for the war. In Sarajevo, Princip is a terrorist, while in East Sarajevo, he is a hero. The schools teaching these two versions are just a few kilometres apart. Back in the day, Yugoslav history books used to teach us that he was a Yugoslav nationalist “aiming for the unification of all Yugoslavs”, as he said during his trial.

|

By teaching different versions of history in separate schools, education systems in the Balkans are creating a generation of young people who have completely different versions of reality.” |

It is clear that, at the moment, different ethnic groups in the Balkans cannot reach consensus over the assassination and the role of those involved. It is also highly improbable that in the near future a uniform answer will come up on whether Princip was a patriot or a terrorist? This also highlights the difficulties of finding a common ground when discussing the most recent war in Bosnia, or any other historical occurrence in the region.

By teaching different versions of history in separate schools, education systems in the Balkans are creating a generation of young people who have completely different versions of reality, different convictions and deep disagreements over these “right” or “wrong” interpretations of the past.

These disagreements are visible now as the commemorations of the event are planned. In Sarajevo, the attempts to organise a range of cultural and peace events in the city have been driven mainly by foreign embassies and individuals. The state has once again failed to use the occasion to promote cultural diversity and reconciliation.

Instead, the commemorative events on June 28 indicate the extent to which they have failed. Although last year it was speculated that a number of foreign dignitaries would attend the commemoration, it is now clear that this is not the case. Serbian Prime Minister Vucic and President Nikolic has decided not to come to Sarajevo, because the board at the Town Hall where the commemoration will take place makes mention of the “Serbian aggressors”. Serbs from Republika Srpska also will not attend.

They will, however, attend the commemoration in Visegrad, where a famous film director from Sarajevo, Emir Kusturica , is opening Andric-grad (City of Ivo Andric), in memory of the famous Nobel Prize winner, Ivo Andric. On the eve of the centenary, as the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra plays in Sarajevo, Russian Alexandrov Ensemble will perform in Visegrad.

Commemorations in Belgrade and East Sarajevo will also include the raising of a monument to Gavrilo Princip. In the Federation, a monument to Franz Ferdinand was planned last year, but the local authorities have not followed through.

“If there is ever another war in Europe, it will come out of some damned silly thing in the Balkans,” Otto von Bismarck famously said in 1888.

Although the Sarajevo assassination is often seen as the event which marked the start of the Great War, European academics agree that the roots of the conflict are much deeper: The imperial ambitions of the European powers, growing militarism, military alliances, the bitterness resulting from the Berlin Congress, and growing nationalism, in the Balkans but also throughout Europe. Balkan academics, however, cannot reach such a consensus.

A hundred years after the war, the question remains: What – if anything – have we, in the Balkans, learned from history? Judging by contemporary political rhetoric – very little, it seems.

Lana Pasic is an independent writer and analyst from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Follow her on Twitter: @Lana_Pasic