China ramps up ‘pressure tactics’ as Hong Kong protests push on

Beijing accused of intensifying arbitrary detentions and phone inspections at the border to contain weeks-long protests.

As anti-government protests in Hong Kong push on into their 12th week, Beijing is intensifying “intimidation tactics” on lawyers, journalists, and diplomats travelling to and from the mainland in an effort to contain the gravest threat to Chinese authority in decades.

There has been a spike in reports of detentions and phone inspections among individuals suspected of involvement with the protests who have travelled to mainland China in recent weeks.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHong Kong’s new security law comes into force amid human rights concerns

Hong Kong passes tough new national security law

What is Article 23, Hong Kong’s new draconian national security law?

“Overall, it’s clear that all Hong Kongers should be cautious about travelling to the mainland, where police have sweeping powers to detain individuals suspected of political activity on arbitrary grounds and with fewer safeguards against torture and mistreatment,” says Frances Eve, deputy director of research at Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD), an NGO based in Washington, DC.

|

|

One of the most prominent cases was that of Simon Cheng, a 28-year-old Hong Kong resident and staff member of the British consulate, who was detained by Chinese authorities on August 8.

Cheng, a trade and investment officer at the consulate’s Scottish Development International section, had travelled from Hong Kong to the neighbouring mainland city of Shenzhen for a business meeting when he was placed in administrative detention for 15 days “as punishment” by Shenzhen police for breaking a public security law.

China has accused the United Kingdom and the United States of instigating the protests.

Cheng reportedly returned to Hong Kong on Saturday, according to a Facebook post from his family.

Cheng’s girlfriend told CNN that Cheng is both a Hong Kong permanent resident and a holder of a British National Overseas (BNO) passport, a special document granted to people the former British colony. A BNO entitles holders to UK consular assistance but it does not equate to citizenship.

The Chinese government does not recognise dual nationality for Chinese nationals.

In a press conference last Friday, China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Geng Shuang said it made “no sense for the UK to raise concerns” because Cheng’s case “is entirely an internal affair”.

“We urge the UK to stop wantonly commenting on Hong Kong-related affairs and stop interfering in China’s internal affairs.”

State-media claimed Cheng was being held for “solicitation of prostitution.”

Eva Pils, law professor at King’s College London and expert on human rights in China, told Al Jazeera, that Cheng’s case “is a fairly common way of trumping up charges to be able to detain somebody”.

“There’s a kind of extra-legal, lawless way of controlling critics, human rights defenders, and so on.”

‘Detention trend’

On Friday, the Canadian consulate in Hong Kong suspended all work travel to mainland China following Cheng’s detention.

After coming to Hong Kong to observe the protests, Beijing-based human rights lawyer Chen Qiushi, 33, was forced to return due to pressure from authorities, the South China Morning Post reported. Videos documenting the protests and uploaded to his Weibo account, where he has 770,000 followers, were deleted.

|

|

“In terms of Chinese activists and lawyers, we have received several reports of mainland supporters of Hong Kong being visited by police, threatened into deleting social media comments, and some that have been administratively and criminally detained,” says Eve of CHRD.

Chinese authorities had implemented a similar crackdown during Hong Kong’s Occupy Central movement in 2014, during which protesters called for universal suffrage.

According to CHRD, that year, Chinese authorities detained 212 individuals who commemorated the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre or supported the Hong Kong demonstrations.

Several were given prison sentences of four to five years.

The following year, China launched one of its harshest crackdowns on human rights in decades, with some 300 rights lawyers and activists detained, interrogated or threatened. It is known as the ‘709 crackdown’, referring to its start on July 9, 2015.

While the number of detentions has not been as high this year as it was five years ago, the suppression of human rights defenders “has increased dramatically,” says Eve.

“A lot more human rights defenders are in prison or may not speak out on social media for risk of being detained.”

Since President Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, China has intensified its crackdown on dissent and tightened control over the media, online speech, religious groups, and civil society.

Now, these control techniques are beginning to develop a “cross-border dimension,” says Pils.

“There’s absolutely an increasing trend to detain not only Chinese people, but also foreigners.”

‘Delay and intimidatory tactics’

This week, a group of journalists from British news agency Sky News were also briefly detained in mainland China.

Beijing-based Sky News Asia producer Michael Greenfield was travelling overland from Shenzhen to Hong Kong with two colleagues when he was detained on Monday.

|

|

He says immigration held him for over an hour, ostensibly because of “a problem” with his visa that “needed to be researched”.

Greenfield – who is on a J-1 visa, issued to resident foreign journalists by China – was kept in a room where his phones remained in sight but he was not allowed access to them.

“It felt like delay and intimidatory tactics,” he wrote.

Greenfield’s colleague, Beijing-based Asia correspondent Tom Cheshire, was detained on Thursday while travelling to Beijing from Hong Kong.

Cheshire, also on a J-1 visa, says officials searched his three phones, went through photos of what they called the “reactionary protests” and asked if he had taken part. On his Chinese phone, they took a “cursory” look through his WeChat.

While his request to call his embassy was not denied, he says officials seemed to want to delay it.

“It’s definitely worrying. They’re trying to show you a bit of muscle,” Cheshire told Al Jazeera, adding that he has never felt direct intimidation like this.

“It’s clear that Hong Kong has become one of those topics,” he told Al Jazeera; the pressure on western media “feels like a more concerted campaign”.

China sent a letter on Tuesday to more than 30 foreign news outlets in Beijing, urging them to be”impartial” and “objective” in reporting on the protests, saying it was their “due social responsibility” to help “protesters ignorant of the truth to get back to the right path”.

In a statement, the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China wrote on Saturday that it: “Strongly condemns any use of border powers by Chinese authorities to target properly-accredited journalists for search and detention.

“Unnecessary and arbitrary searches constitute intimidation and harassment and hamper correspondents’ ability to report freely and openly in mainland China and Hong Kong.”

Fear of the Hong Kong protests

Since June, protests have raged across Hong Kong in opposition to a now-shelved bill that would have allowed the extradition of individuals to mainland China to face charges and trial there.

|

|

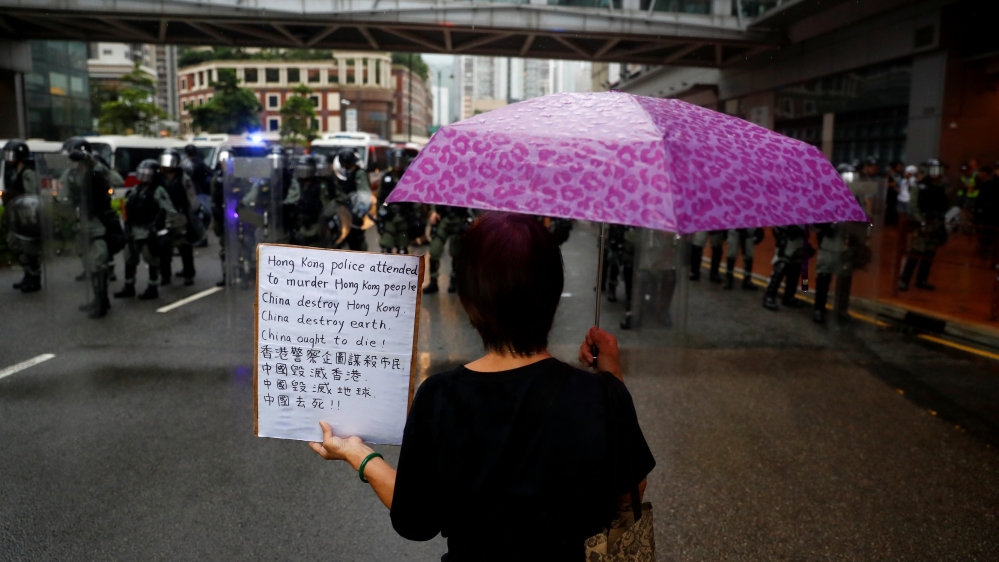

The mass demonstrations, some drawing millions, have transformed into a wider movement against Chinese interference and the erosion of Hong Kong’s cherished civil liberties.

On Sunday, protesters clashed anew with police, and for the first time, authorities used water cannon to disperse protesters.

Several reports have also surfaced of Hong Kong residents being required to unlock their phones at the Chinese border for inspection of their photos and videos related to the protests, a deliberate and “highly visible” threat, says Pils.

China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the National Immigration Administration, and The Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office of the State Council did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

“One must understand the degree to which central authorities must be concerned about the risk that this spark of protest in Hong Kong spreads across the border,” says Pils.

“That will translate to all kinds of instructions and directives to border control to make sure they control… this interaction between Hong Kong and the mainland.”