Online free speech vs private ownership

Unlike the town square, social media sites are privately owned and have rights over content that is posted.

|

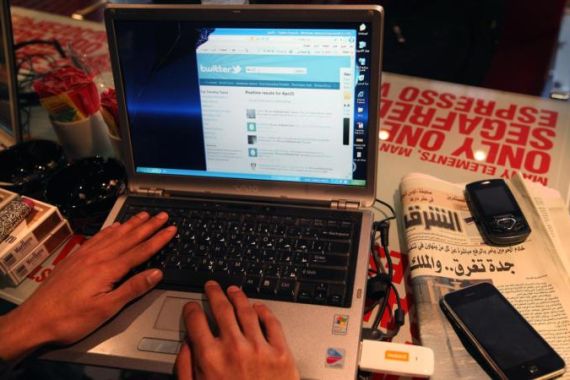

| Like most of the social media landscape, Facebook and Twitter are private companies which ultimately decide what content can be posted on their websites [GALLO/GETTY] |

Free expression, as defined in my home country, the United States, and by Article 19 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, does not apply to privately-owned spaces. In the past, this conundrum has led to controversy and, occasionally, court cases regarding company towns and shopping malls.

As our conversations and calls for protest move from the so-called town square to the quasi-public sphere that is social media, similar concerns arise. We easily forget that Facebook, Twitter, Blogspot, and every other place where we conduct our business online is privately owned, and that, by investing our time and content in this sites, we are allowing their staff ultimate control over our speech.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHong Kong’s first monkey virus case – what do we know about the B virus?

Why will low birthrate in Europe trigger ‘Staggering social change’?

The Max Planck Society must end its unconditional support for Israel

As evidence over recent months has shown, there is reason to be concerned: In November, the much-lauded “We Are All Khaled Said” Facebook page was temporarily removed because of a terms of service violation (its now-famous administrator, Wael Ghonim, had used a pseudonym). Just a few weeks later, corporate giant Amazon removed WikiLeaks from its hosting service after pressure from Senator Joseph Lieberman.

Less often discussed is the fact that groups regularly band together to target specific content for removal, particularly on Facebook. Since I began monitoring this issue, I’ve seen a variety of actors call for content to be reported for removal: Muslims targeting Arab atheist groups, Jewish groups targeting pro-Palestinian content, liberal groups targeting Sarah Palin, and the list goes on.

Sometimes the reports are justified, at least as they pertain to a given site’s terms of service, whereas other times they could be likened to bullying. More often than not, they fall somewhere in between.

Terms of use

One recent example of such involves Israeli activists who targeted the Facebook page of the Oz Unit of the Immigration Police for removal after a video was posted showing the deportation of foreign laborers and their children. A report on a Hebrew-language blog states that a call from Israeli anti-deportation activists to report the Facebook page for “racist content” (a terms of service violation) was successful in removing the page, which had over 400 fans.

Similarly, a Facebook page calling for a third intifada in Palestine was removed in April after pro-Israel activists called for its removal on blogs and Twitter. Their cause was supported by an Israeli minister who wrote to Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg to request the removal of the page. Though Facebook publicly responded, stating that they would not remove a page unless it contained content in violation of their terms of service, the page was eventually removed for “incitement to violence.”

But in both cases, the effects were short-lived. A new version of the Oz Unit page has already cropped up. The Third Intifada page was replicated numerous times, resulting in what is often referred to as the Streisand Effect, so named for an incident in which actress Barbra Streisand attempted to suppress photographs of her residence online, generating extensive publicity that the incident likely wouldn’t have received otherwise.

Israeli activists continue to call for the removal of another page, this time that of the Population, Immigration & Border Authority in the Ministry of Interior.

Various groups have, at times, used the Facebook platform to set up groups for the specific purpose of targeting other groups for removal. With names like “Report It” and “Facebook Pesticide”, these groups have seen limited success, but often find their own pages taken down.

This strategy of targeting pages for removal is, in a sense, similar to the strategy used by hack-tivist collective Anonymous: Following Amazon’s takedown of WikiLeaks and the refusal by Visa and Mastercard to accept donations to the whistleblowing site, Anonymous targeted their websites with distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, which effectively took down the sites for a short time.

Calls to remove Facebook pages serve a similar purpose, and potentially take advantage of a flaw in Facebook’s content management system. While Facebook representatives have at times stated that a large number of reports can trigger automated removal of content, at other times they have stated that their systems are designed in such a way that targeted campaigns will not trigger removal.

Civil disobedience?

Whether or not this – and the DDoS attacks used by Anonymous – is a valid tactic of civil disobedience was the subject of discussion at a December forum on WikiLeaks. While some, like Deanna Zandt and Evgeny Morozov, have written of DDoS as a legitimate but limited tactic, others – such as Ethan Zuckerman – have concerns that legitimising DDoS as a form of protest helps legitimise its use against human rights and independent media sites as well.

Indeed, every potentially legitimate takedown could be considered an attempt to silence truly legitimate speech. Therein lies the problem: By deeming social media the new “public sphere”, we have left such decisions up to the automated systems and undoubtedly low-ranking staff of private companies, which have no vested interest in preserving the principles of free speech.

But then, whose decision should it be? Laws on what constitutes legitimate speech vary from country to country, and the United States – where the vast majority of social media companies are based – has some of the most permissive laws when it comes to free expression. American companies – unlike, in many cases, European ones–are not responsible for most content published on their sites thanks to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. As a result, such companies are often more permissive than their foreign counterparts.

On Facebook, this has led to outrage from parties around the world who think the company should do a better job of policing content. Facebook’s own policies – such as one that bans images of mothers breastfeeding–has also angered users, illustrating the difficulties faced by the company in determining what to allow and what to remove.

As I have written previously, it is a complicated question with no easy answer. Although private companies are ultimately the arbiters of appropriateness when it comes to their online spaces, I believe that American companies like Facebook, Google, and Twitter should lead the way in implementing policies that advance free expression online. To that end, they would to well to ensure their systems aren’t being abused by parties who would rather silence free speech.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.