Ebola in retreat in eastern Sierra Leone

Outreach efforts and high risk of death prompted a change in attitude towards the virus and drop in new infections.

Kenema, Sierra Leone – At the main government hospital in the eastern town of Kenema the sense of relief is palpable. Builders repaint the peeling walls of the now-empty Ebola isolation ward, while protective suits smoulder gently on a bonfire behind the building.

It has been a month since Kenema district recorded its last case of the deadly Ebola virus on November 1. Although officials insist that vigilance is key to keeping the district Ebola-free, it is clear that part of the battle has been won.

“We are so happy the disease has gone far from us,” said Nabil Moussa, who for months worked inside the isolation ward. “We were afraid, but now can relax a little.”

For several months after the virus crossed the border from neighbouring Guinea in May, Sierra Leone’s eastern districts of Kailahun and Kenema bore the brunt of the epidemic. The number of cases rose rapidly, and at one point Kenema was recording more than 50 new infections per week.

Dozens of health workers at Kenema’s hospital were dying, and families were being decimated in villages throughout the district.

Overall, the ongoing Ebola outbreak has killed more than 7,000 people – almost all of them in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea – and the World Health Organisation recently reported a sharp rise in deaths from the virus. More than 16,000 people have been diagnosed with the disease since the outbreak was confirmed in the forests of remote southeastern Guinea in March.

|

| Men reflect in a village in Kenema district in eastern Sierra Leone where dozens have died of Ebola [Tommy Trenchard/Al Jazeera] |

But although the number of infections in Sierra Leone has spiked, most cases are concentrated in Freetown, the capital, and surrounding areas in the country’s west.

Dramatic turnaround

In eastern Sierra Leone, the trajectory had seemed clear: The virus was spreading exponentially and efforts to control it seemed to be falling further and further behind. Anja Wolz, the head of Doctors Without Borders’ (MSF) operations in Kailahun at the time, said Ebola was always two steps ahead of efforts to contain it. But four months later, the turnaround in the district has been dramatic.

The trend is similar in neighbouring Liberia. All of the areas that suffered from high rates of Ebola during the early part of the outbreak are now seeing a marked decline in new infections. In August, people were dying of Ebola outside packed treatment centres in Monrovia, Liberia’s capital. Now those same centres are not even half-full.

Michael Vandi, a health education officer for Kenema district, said the key to the decline in new cases was a wholesale shift in the public’s perception of Ebola and those fighting it.

“They used to cuss us in the street and call us liars,” Vandi recalled from the early days of the outbreak, when suspicion about the disease was widespread. Fear of health workers caused many sick people to avoid Ebola treatment centres, and ignore basic health advice that could have stopped the spread of the virus.

Pariahs to heroes

Now, those same people treat Vandi like a hero for his role in fighting the outbreak. “There’s nowhere I go in this town now where people don’t heap praises on us. It happens every day,” he said.

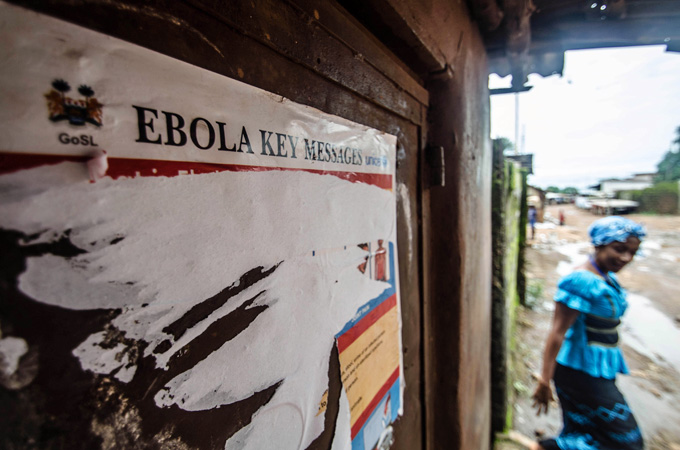

|

| Ebola continues to rage in western and northern Sierra Leone [Tommy Trenchard/Al Jazeera] |

Public perception of the virus has changed dramatically, according to Vandi, and unsafe burial practices – which are believed to have been a major source of Ebola infections during the outbreak – have been curbed. Despite the absence of new cases of the virus, the burial teams in Kenema remain busy. Wary villagers now call them in to safely bury their dead relatives, even when there is no sign of Ebola.

Vandi added that hand-washing has also become “part and parcel of people’s lifestyle”.

Last month, villagers who realised they may have come into contact with Ebola after an unsafe burial, chose to isolate themselves in a school building with other potentially infected people, despite the risks of contracting the disease there.

“That would never have happened a few months ago,” said Andy Ramsay, the WHO coordinator for Kenema during the crisis period.

Ramsay pointed to a strict system of quarantines and isolation measures that helped interrupt the virus’ transmission, as well as a massive outreach programme that sought to persuade people to adopt preventive measures.

‘Devil business’

But perhaps the most important factor was simply that for months on end, residents of the district were surrounded by death. Eventually, almost everyone knew somebody who had died of the disease.

|

| A health team prepares to bury the body of a potential Ebola victim [Tommy Trenchard/Al Jazeera] |

“They saw evidence of what was happening,” said Vandi. “They saw their loved ones sick. Their friends died, their relatives and neighbours died.”

In Freetown, which witnessed almost no cases for the first few months of the outbreak, similar efforts to educate residents about Ebola and its dangers have had far less impact, and as a result transmission rates remain high.

People routinely hide their sick relatives from authorities and continue to attribute deaths to witchcraft. “This devil business,” as one bereaved resident of Waterloo told Al Jazeera.

Why the difference between Kenema and Freetown, which have both been subjected to the same unrelenting education campaign?

The level and duration of exposure to the virus seem to be key factors. The situation in Kenema suggests Ebola can ultimately burn itself out – the more deaths it causes, the more people choose to change their behaviour.

“People just became aware [of the virus],” said Kenema resident Mohamed Amara, 24. “It didn’t happen quickly, but now they’ve seen a lot of people die.”

|

| In contrast to eastern Sierra Leone, health advice still goes largely unheeded in the west [Tommy Trenchard/Al Jazeera] |